As with the Erik Larson's "Dead Wake" (about the Lusitania), the basic outline of the Wright Brothers story is well know. (I mention the Lusitania as I was concurrently reading "Dead Wake" - Erik Larson about the Lusitania; it was odd to see that when the Wrights flew a demonstration in New York, the flew around the Statue of Liberty and right over the decks of a loaded Lusitania).

McCullough's book is good, and covers the story, but I didn't find that the story had enough drama to make the book as compelling as I might have liked for a summer read. A the turn of the century (19th to 20th century) a debate raged about whether or not "heavier than air" travel was even possible. Balloons, Dirigibles and Zepplins flew using hydrogen (and later helium) and hot air to make the craft ascend, but powered aircraft were an unknown.

There were no lack of inventors - France, in particular, hosted many, and the U.S. had several of their own. I suspect that knowing the outcome, the drama of the "race" was somewhat lost.

The Wrights were cycle mechanics, and generally well rounded mechanics and engineers. They set about studying birds and how their wings worked, and researched all that was to be found on attempts with gliders and other craft. They were surprised at the lack of detailed understanding of the science and the engineering that was known at the time.

My image of their first flight was on a beach in North Carolina, likely near a town, with a crowd watching off-frame from the famous photograph. I was very surprised to find Kitty Hawk was very isolated and took days to reach by boat and hiking, and was a very small settlement of fishermen. Impressively, the Wrights had to build a shop at Kitty Hawk, and survive pretty fierce storms, heat, cold and mosquitoes depending on the month, with only the help of a few locals. What Kitty Hawk had going for it was reliable winds running pretty much constantly, small hills to provide a launch opportunity, and sand to provide a less deadly landing environment.

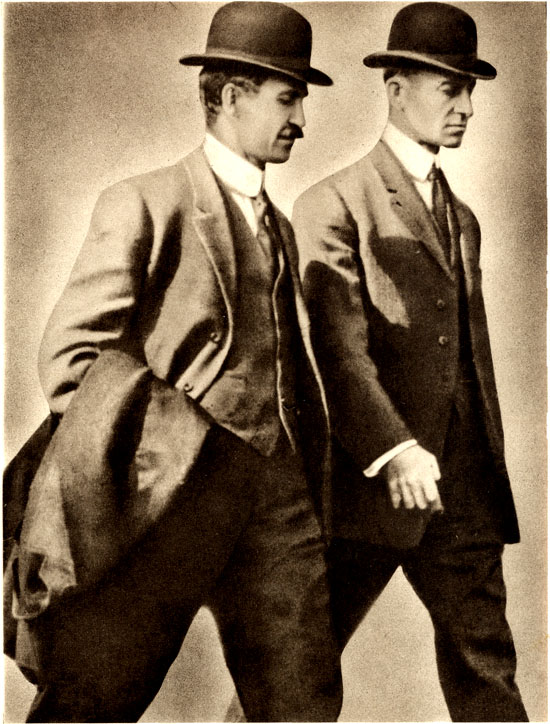

When the Wright's created a plane that worked, they used it to get money for invention - the primary sources were contests (e.g. anyone who can fly for 10 minutes wins $10,000 type events) and military contracts. The first to express interest were the French, who were worried about their German/Austrian neighbours. The Wrights were to receive money if they successfully demonstrated their invention. Thus, Wilbur went overseas to demonstrate the aircraft.

Both brothers had crashes, though neither died from them (I had always though Wilbur died in a crash for some reason). Wilbur died of Yellow Fever in his 40's, and Orville lived into his '70s, having seen what his invention was capable of doing in wartime. Though Orville didn't like the destruction his invention could cause, and the blurring of what are wartime targets that came along with it, he never regretted the invention itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment